by Kevin Larrabee, CSCS, CFSC, PN-1

Above is the audio version of this article with some additional commentary.

Download the audio file by right clicking here (option-click on Mac) and selecting save-as)

Preface

First, thank you for taking the time to read what in today’s world is a lengthy article (that is why I put it in audio form as well), but for athletes, coaches, parents, strength coaches, trainers and fitness enthusiasts this information could change your and or an athlete’s career. It is my goal that this article will make you change the way you think about speed and performance training as well as the importance of smart and effective programming in reducing the risk of injury in youth athletes.

This article mainly covers four subjects:

- The Reality of Youth Athletics

- Deceleration’s Role in Athletic Speed and Performance

- Athlete Injury Rates

- The Mental and Social Impact of Injury

I believe we need do everything possible to reduce the risk of injury in youth athletes. It has become far too common that as part of a youth athlete’s career they will experience a serious injury requiring surgery or significant time off from their sport. It can be devastating for that athlete. Think of it this way. If you are a Sophomore in high school and tear your ACL during the first game of the fall soccer season, you could end up missing 25% or more of your high school career. Think of that, 25% of one’s athletic career. With that time off, if you aimed to play in college, that goal might seem less attainable. That injury may increase your risk of another injury or reduction in performance. It could even change an athlete mentally, having an impact on their academic and social life. While we will focus on performance, at this point it should be clear that we will be talking about its relationship with injury prevention.

What started as an article on deceleration’s importance in sports performance and injury prevention, it quickly expanded to include a more in depth look into the reality of youth athlete injuries. It is by far the longest thing I have written since my Senior Thesis in college. I hope you find this article valuable and that it may get you to change the way you conceptualize performance training. Now, let’s start by talking about the state of sports performance training for youth athletes.

The Reality of Youth Athletics

For youth athletes, aside from height (depending on the sport), coordination, speed and strength (obviously as well as their ability in the sport) will be what separates the good from the great. And today athletes, parents and coaches are bombarded with speed development camps and conditioning programs consisting of a random assortment of hurdle drills, agility ladders, sprint variations, long shuttle runs and so much testing and data it makes the NFL Combine look like peewee football tryouts. I am not saying that those drills and tools aren’t effective and needed, but first you need a system. And some coaches and facilities will use a barrage of assessments and testing as a sales tool or as proof of how “elite” their program is. I understand why you might do that, but I ask that you step back and look at the bigger picture. For an athlete under 16, do you really need to know their vertical leap? How about their 40-yard time? More importantly, do you need to line them up every week with their parents and peers looking on to test them to check in on progress? Is that a good use of your training time? Should we put into account how all this testing will affect them socially and psychologically, drawing comparisons with their peers of various ages and states of development? Before I get 100 emails and DMs about how this is being too soft on athletes, in some cases you may be right, but we can’t ignore the reality of today’s youth athletes. If you have an athlete that is playing in multiple leagues and is in some sort of training program do you think they are lacking in feedback and criticism? Also, there is always the unspecific statement of “it depends.” You wouldn’t necessarily communicate or coach an 18-year-old football player the same way as a 11-year-old baseball player or a 13-year-old field hockey player. If you want to connect and get “buy in” from athletes, you need to be flexible in your coaching style and communication. Flexibility in communication style is one area when athlete or sports specialization makes sense.

Now back on topic. This doesn’t mean that “speed training” isn’t important, or doesn’t have a place in athletic development, far from it. But maybe we need to look at it from a different angle than programming ladder drills, sprint variations, and testing out a 10-year old’s broad jump to get them ready to compete at a high level.

Deceleration’s Role in Athletic Speed and Performance

Fast and healthy (more on this later) athletes aren’t just great at acceleration. They are equally great at deceleration. This is literally how fast athletes become so good at change in direction and to reacting to a defender 1 on 1. Athletic speed is a combination of your ability to exert force on the ground to accelerate, and then reabsorb and/or transfer it for deceleration and change in direction. On the court, field or ice, one’s ability to accelerate in a straight line isn’t all that useful without that balance of their ability to decelerate. There are few real applications to pure linear acceleration in sport such as a wide receiver running a “fly” route or for specific track events.

Since I am a big fan of the Fast and Furious franchise, I like to use the performance car analogy. At the end of the day, it becomes irrelevant how strong of an ENGINE (think concentrically working: calves, glutes and quads) you can put into the car unless you can pair it with equally strong, as well as reactive BREAKS (think eccentrically working: mainly glutes, quads and hamstrings as well as abductors/adductors) for deceleration to make tight turns and abrupt stops. What happens if you can’t slow down and reabsorb that momentum you have built up in acceleration? Best case scenario, you don’t make the play or look a little uncoordinated. But potentially, especially in a fatigued state (think the last 25% of a game or practice as we know the more fatigued an athlete is the more likely an injury is to occur), a non-contact injury occurs such as an adductor or hamstring pull. At the extreme we witness a more severe non-contact injury such as an ACL or MCL tear. While I specifically point out non-contact injuries, great programming can also make an athlete (or adult) more resilient to contact injuries as well. Similar analogies can be made with the upper body including such as elbow, neck and shoulder health, but for this article we will be focusing mainly on the lower body.

Engine being concentric hip and knee extension as well as plantar flexion. Breaks being eccentric hip and knee flexion as well as dorsiflexion.

Let’s break down this concept by briefly defining what I believe are the three most important components of athletic speed.

Coordination– Body awareness. This can also be described as “footwork.” Coordination in its nature has a declarative component. This is where tools like agility ladders and reactive change in direction drills can be of great use.

Controlled Power Output– How much force you can produce and exert on a surface with the goal of CONTROLLED acceleration. This is where drills like linear sprints, weighted sled sprints and marches as well as lower body strength training comes into play.

Controlled Deceleration– The ability to absorb force through your musculoskeletal system (body and its tissues) with the goal of controlled deceleration. This is mainly in the pursuit of change in direction and landing from vertical leaps (two legs) and bounds (one leg). Programming for this skill would consist of sprint drills with a deceleration and change in direction component, well coached and programmed plyometrics and both normal tempo and eccentric lower body strength training.

While all three are critical to athletic performance and health, the last component, Controlled Deceleration is the most neglected by coaches and programming. In Part 2 of this series we will look at how to build better programming systems to address this.

Athlete Injury Rates

In writing this article, I knew from the start that having “deceleration” in the title would make this article less attractive for some readers, I would have to make it a bit more exciting to get your attention. But a big motivation for writing this was from the lack of attention deceleration gets from other experts when discussing speed and sports performance programming and training, especially its importance in reducing the risk of injury. It is more than doing some glute activation drills with a band while warming up, again much more on this in part 2.

Commonly, the #1 goal of trainers and strength coaches has been the same as the first pledge of the Hippocratic Oath. An oath taken by doctors and those in the medical field. That pledge is “First, do no harm.” In the world of fitness and sports performance training we have adopted this to mean that no adult or athlete should ever get injured in your facility due to the coaching, environment (think equipment choices, layout and flow) or programming (exercise selection and progression). This is a GREAT goal, and it should be front of mind for every fitness professional. But I think this should be obvious. A given. But, the obvious isn’t always obvious. This goal should at least be expanded on, especially for athletes. Our #1 goal should be to Reduce the Risk of Injury. This goes for both contact (collision with another athlete) or non-contact. To keep the athletes we have competing and out of the ER and rehab facilities. If you don’t get a knot in your stomach when one of your adults or athletes gets hurt outside of the gym, you might be in the wrong profession. They are entrusting their career and health to you. It doesn’t matter if you are coaching a $200 million pitcher or a 14-year-old hockey player. Treat that responsibility with the weight it deserves.

Sorry to get really serious for a moment, but it’s the truth. The good news is that smart programming and good coaching will net the athlete a reduced risk of injury while also improving performance. Win-win.

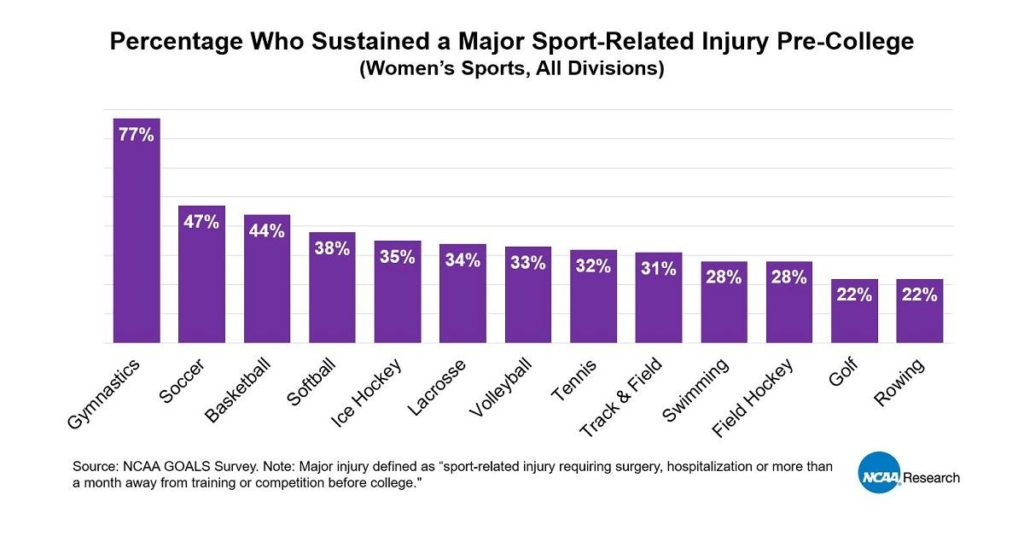

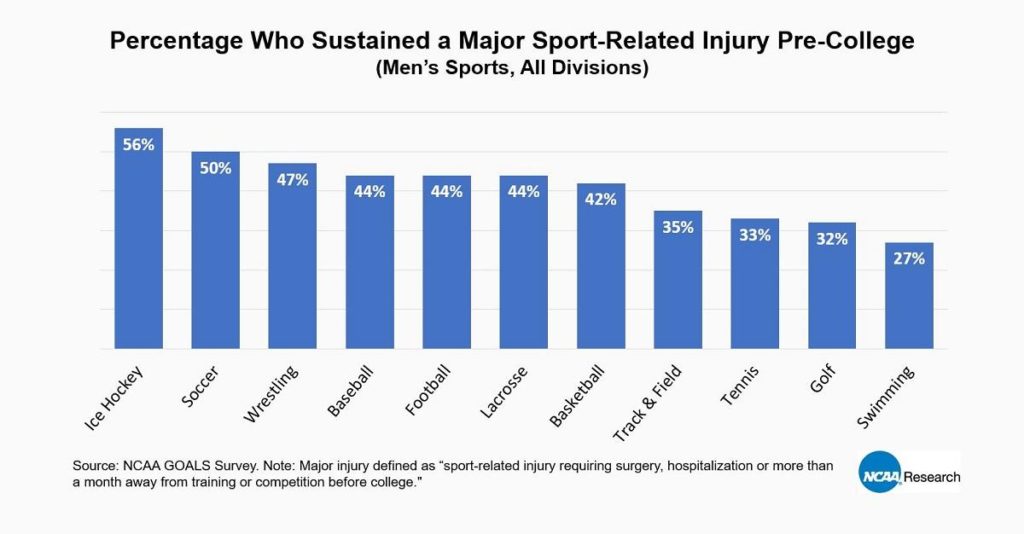

A Brief Look at Recent Pre-College Injury Rates

Per NCAA Research, 42% of NCAA men and 36% of NCAA women “sustained at least one major sports-related injury before entering college.” Keep in mind that this does not take into account middle and high school athletes that DO NOT participate in NCAA sports. My guess is that number is even higher for athletes that do not go on to play in college. This NCAA research defined “major injury” as a “sports related injury requiring surgery, hospitalization or more than a month away from training or competition before college.” This same research acknowledges the data showing the harm of early sport specialization and the need for off court/field/ice development and strength training.

For men the three sports with the highest rates of injury were Ice Hockey (56%), Soccer (50%) and Wrestling (47%) while Baseball, Football and Lacrosse were all tied for 4th (44%). For women the top three sports were Gymnastics (77%), Soccer (47%) and Basketball (44%). An interesting thought and conversation for another day would be to look at sports with higher injury rates like gymnastics and how these sports of attrition tend to neglect less athletic athletes who tend to drop out due to repeat injuries and body types as they mature.

These injury numbers should concern any athlete, parent or coach participating in youth athletics. Research like this has been a driving force in required off court/field/ice developmental time for youth athletes who have often been spending far too much time playing their sport (usually in multiple leagues) and not participating in a strength and conditioning program. Ice hockey, soccer and basketball (AAU) are some of the best examples of this.

Today there is no lack of research and statistics on the injury rates in youth athletes. It is great that we are getting more and more date to help athletes, parents and coaches make better decisions for the athlete.

The Mental and Social Impact of Injury

Down the road I will be expanding on the mental and social impacts of injury in more depth. They absolutely deserve more attention from strength coaches. But for today, here is a brief breakdown. When an athlete sustains a serious injury, even injuries not requiring surgery, it is not just a statistic or linear path towards recovery. In a perfect world, if an athlete gets hurt it would be a simple 3 step process:

- Athlete gets Hurt

- Athlete gets the Injury Repaired/It Heals

- After Designated Rest and Rehab Athlete Returns to Play at 100%

That’s not how it works out. We can take an x-ray to see how the bone healed. We can use an MRI to see how the ACL repair grafted and test for anterior knee pain and stability. We can go through the rehab protocol and conclude that the injury has fully healed. Does that mean they are ready to return to normal play? Outside of the physical recovery, coinciding with the injury are mental and social impacts that are often overlooked by doctors, coaches, parents and even the athletes themselves. So, let’s do that now.

Mental Impact:

When returning from injury, athletes regularly experience a lack of trust in their bodies ability to perform as it once did. Usually, if an athlete gets their injury treated and follows the recovery protocol and or rehab, they will return to play on schedule and without residual effects or pain. But for some athletes, especially if there either wasn’t a proper rehab program to rebuild strength and stability, they may return to their sport without effectively preparing and testing the affected area. When this happens, there is usually a lack of trust in one’s body leading to reduced performance, a recurrence of the injury, and most likely movement compensations that may cause different injuries. A pulled hamstring is a great example of an injury that tends to be recurring for athletes throughout the season. It is one of the reasons I put together my “Building Strong Breaks” seminar to discuss the importance of declarative training in speed drills, plyometrics and strength training.

It is pivotal that athletes do not rush their recovery and they are open with their circle of coaches, parents and specialists about their progress. There is also the much more complicated mental component of reliance on anti-inflammatories and pain killers that deserve a longer and separate discussion for another day. But it can’t be stressed enough, we need to remember that opioid addiction is real and a prevalent concern.

Social Impact:

The social impact is really a branch off of the mental changes due to injury. For some athletes, their sport and participation is a significant part of their identity. When they get injured and they are not able to participate like they have become accustomed to, it can cause a disturbance in their personality and social life. This is usually due to isolation when recovering at home from the injury or surgery. They aren’t in their regular routine of school, practice and games. They aren’t with their friends and team mates. They could also feel like they let their team down or similar feelings from not being able to participate. During this time, it is important for their family and social circle to make an extra effort to keep in regular contact and help the athlete return to something close to their normal social routine as soon as possible. It is important that they can always see the light at the end of the recovery and rehab tunnel. As coaches we need to keep this in mind.

If you would like to know more, Margot Putukian, who is the director of athletic medicine and head team physician at Princeton University wrote a great article about it in the NCAAs handbook for athletes titled “Mind, Body and Sport.”

Part 1 Wrap Up:

Hopefully it has become clear how passionate I am about our responsibility to do whatever we can to reduce the risk of injury, but this article’s focus is on performance. Again, smart programming and coaching produces an athlete that is not only able to perform at their best, they are also going to have a healthy and successful career. Since this is already close to 3000 words, we will look at programming and practical application of deceleration training in part 2. Please feel free to send any follow up questions or comments to me via email or social media.